Coastal View News

There are all sorts of ways to scare someone. You could

jump out at them. You could gross them out. You could make them feel unsafe. Or

you could give them an itchy, eerie, creepy feeling—make it a skin-crawling spook

fest.

Or you could strip away all that—all the gore, the goons and

ghosts and goblins; the fog and cobwebs and blood—and do something more basic,

more primal. You could give them a snapshot of people in isolation. Of the

inherent frailty of the human mind. Of what it is like to be unhappy, lonely,

guilty, angry, resentful. All you have to do, really, is show them what it is

like to be a human when things aren’t going so well.

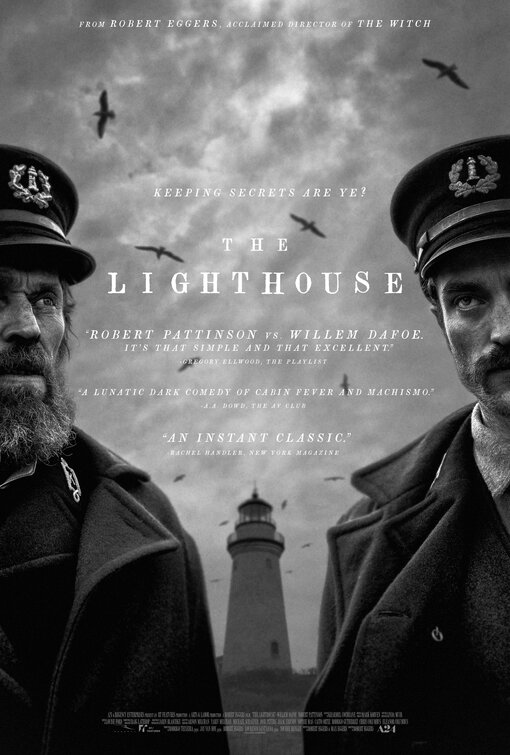

That’s “The Lighthouse.” It’s two men getting stuck at a

lighthouse. That pretty much sums up this move. Just two grumpy, crusty,

sailor-looking dudes, who’ve got no money or education or dentists

(apparently), and who can’t really stand each other, get stranded on a remote

little lighthouse island somewhere in the cold, blustery New England sea.

And yes, absolutely, this is a horror movie.

The first crusty dude—the younger of the two—is Ephraim

Winslow (Robert Pattinson). He arrives on the island to make a little money as

an assistant operating a lighthouse for four weeks. That’s the contract.

Winslow isn’t wedded to the sea or anything. He just needs some cash to set

himself up when he goes home.

The second crusty dude—an old salt if there ever was one—is

Thomas Wake (Willem Dafoe). He’s straight from Moby Dick. When not barking orders, guzzling liquor, and farting,

he tells poetic tales and recites oceanic mythology in a thick, lyrical Irish

accent. He has wild, bushy hair, a full beard, a limp, and a ship tattooed on

his chest.

Right from the get-go, things suck. Particularly for Winslow.

Although he is not too much of a talker, he seems to have hoped for a more-or-less

congenial four weeks sharing duties at the lighthouse. No such luck. Wake

immediately makes it clear that he’s in charge, that he’s not to be questioned,

and that Winslow is to do all of the menial tasks—real grunt work—while he

looks after the lantern atop the lighthouse.

So Winslow carts coal, clears out the (absolutely

disgusting) cistern, patches the roof, oils the gears, and takes out the bed

pans. Then Wake barks more orders, criticizes Winslow, and farts. Over and

over. Day in, day out.

Then things get weird (as if they weren’t already).

Winslow starts having these crazy dreams that include, among other things, dead

bodies, logs, and a super creepy mermaid. And Wake, for his part, has some kind

of mystical regard for the lighthouse lantern. God only knows what he’s doing

up there while on watch.

Things get even weirder. The line between reality and …

well, I don’t know … dreams? Hallucinations? Mere thought? At any rate, it all

becomes very blurry. They’re going crazy, each in their own way. It’s kind of

like “The Shining,” nautical edition. And at no point in the movie does it feel

like things are going to end any better for Winslow and Wake.

Part of that feeling has to do with a pounding fog horn that

batters your psyche like relentless waves harassing the seashore. I’m not sure

whether the fog horn is supposed to be coming from the lighthouse or passing

ships, but, at any rate, it’s a super effective way to communicate pure,

inescapable doom.

The rest of the sound editing in “The Lighthouse” is

equally effective. As is the bleak, harsh black-and-white cinematography. Just

in general, the look and feel of this movie is as striking as it is a perfect

fit for what is going on in the movie. It’s beautifully done—and horrific.

“The Lighthouse” is, like the lives of the island’s two

inhabitants, elemental. It doesn’t get its “horror” designation via anything

too fancy, or jumpy, or gory. It’s more basic—images, facial expressions,

thoughts, and feelings that, in other context, might not be that scary. But, on

that lonesome rock, they chill to the bone.

Director Robert Eggers pulls off a real feat of

storytelling. He taps into the deepest human anxieties and fears without any of

the frills. And the other major players in this film also do a fantastic job.

The actors—all two of them—are great.

“The Lighthouse” is, if nothing else, a cinematic

achievement. It is scary, unsettling, disturbing, shocking, bewildering,

gripping—and all with relatively simple tools. It doesn’t take a blood-soaked,

ghoul-infested fright fest. Just two dudes stuck at a lighthouse.