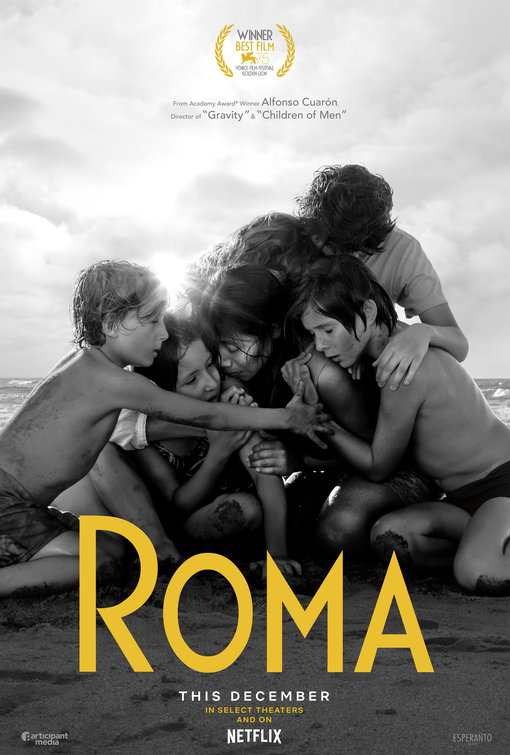

Coastal View News

Cleodegaria

“Cleo” Gutierrez’s (Yalitza Aparicio)

life is, in many ways, not her own. She’s not a slave exactly. She’s a

live-in-maid for a middle-class family in Mexico City in the early 19070s. But

almost everything she does—every decision she makes—she does with an eye toward

her employers’ needs.

Take

the kids, for example. Cleo is basically a second mother (or more like the

first mother) to the four kids in the family she works for—certainly she does

more of the thankless, nitty-gritty work than Sra. Sofia (Marina de Tavira),

the family’s matriarch. Furthermore, when Cleo learns that she herself is a

mother-to-be, among the first things she considers is whether she can keep her

job, how the family will react, etc.

This

isn’t the only part of Cleo’s life that is wrong-way-round. She typically only

gets off work after everyone else is in bed, so her social life is rarified, to

put it mildly. And even the dynamics of the family she serves—strife and

all—affect, beset, and toss Cleo about as if it was her family, her world, her life.

One

could imagine this setup playing out in various different ways. For example,

one could call to mind Alice from “The Brady Bunch”—an ever present part of the

family who is represented as being happy and well adjusted.

On

the other hand, it’s easy to take a more bleak perspective on Cleo’s plight.

After all, she’s a paid actor in others’ drama. She does what others want her

to do, and she does it how they want her to do it. Again, in this way, her life

is not her own. Which sounds bleak.

However,

in “Roma”, Cleo isn’t portrayed along either extreme. The picture is more

complex and nuanced. On the one hand, Cleo’s predicament seems problematic,

unfortunate, and borne of a clearly immoral system. But, on the other hand,

it’s hard to escape the feeling that her life is deeply good—sad but beautiful.

When Cleo, who should have never been in this situation—this life, this

exploitation, this hardship, this unfair and inexcusable ordeal—embraces a

family that is not her own, and clasps them together within her shielding arms,

the feeling is just, thank God Cleo is here.

Now,

of course this feeling is totally problematic. After all, that Cleo is desperately

needed can hardly excuse her subjugation.

It doesn’t somehow make it right, or

even O.K.

But

“Roma” is not about telling you how it is, morally speaking. This is not a

sermon or stump speech. It is a look at the life and spirit, the ups and bitter

downs, of a woman who the world overlooks. It does not depict the triumph of an

ordinary life. Instead it shows its depth. Cleo’s life isn’t glamorous. It is

hard and often boring and sometimes fun but never buoyed by sustained pleasure.

Yet it is not meaningless. Far from it.

“Roma”

is a beautiful film. It is careful and measured. It does not grasp beyond its

reach or stumble into the traps of political or social bloviation. It is

transcendently modest—in its acting, directing, cinematography, and so on. It

cherishes everyday life without exaggerating or even particularly exalting it.

It finds meaning in simple things—not just pleasures, but pains also. This is

the stuff of life.