Coastal View News

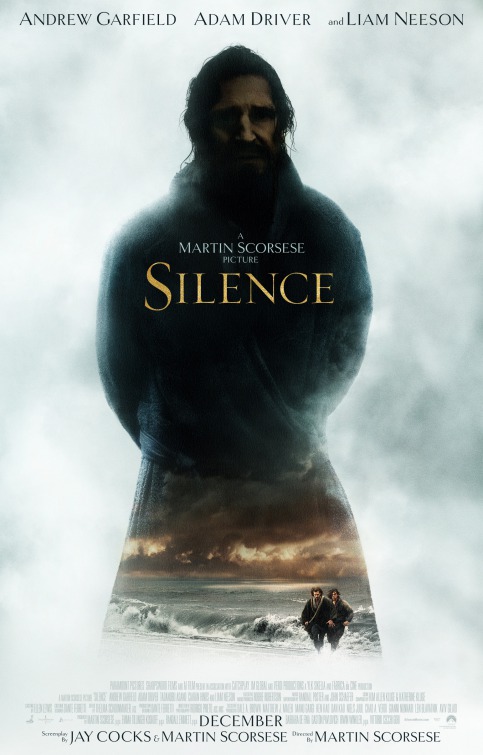

26 years. That’s how long Martin Scorsese was working on “Silence”

before it came out this year. Who knows what took him so long, or why, exactly,

he felt compelled to make it. After all, Scorsese is known for mafia movies,

not religious dramas set in 17th-century Japan (which is what “Silence”

is).

Maybe Scorsese was looking for the right angle—a certain

perspective on this gripping story of two Jesuit missionaries to Japan. Or

maybe he was conflicted about which themes to draw out, which emotions to

evoke, or which message to communicate. There is something deeply personal in

this movie, and something deeply pious—it’s hard to compare it (or anything) to

Dostoevsky’s The Brother Karamazov or

Donne’s Sonnet 14, but it clearly tries

to do something along those lines, as in the tradition of Bergman’s Winter Light or Tarkovsky’s Andrei Rublev.

The story is, after all, ripe for it. Rodrigues (Andrew

Garfield) and Garupe (Adam Driver) are Jesuit missionaries to Japan. Their

long-term goal is to bring Christianity to Japan. Or, rather, it is to bring it

back to Japan. Not long before they

arrived in 1639, there were hundreds of thousands of Christians. But a Japanese

inquisition brought a brutal crackdown. Thousands and thousands of priests and

laity were tortured and killed—beheaded, scalded with boiling water, hung

upside down, drowned, burned alive, etc.

But that didn’t stop the Christians. They went

underground. They worshiped in secret. Jesuit missionaries continued to sneak

in.

That’s not exactly why Rodrigues and Garupe come to

Japan, however. Their mission is rather to find a priest, Ferreira (Liam

Neeson), who was the most devout among them, but who was reported to have

renounced his faith under pressure. In a way, this is the first of many tests

of their faith. Could it really be that Ferreira buckled? Is even the strongest

among them too weak to withstand temptation? They had to know.

And yet when Rodrigues and Garupe arrive in Japan, they

are immediately met with an overwhelming thirst for leadership among the

Christian faithful. These people need their guidance. So they stick around.

And then their second test. The inquisitor, Inoue (Issei

Ogata), comes to town and, suspecting that there are Christians among them,

brutally tortures and kills three men, just to make a point. Rodrigues and

Garupe watch from afar, asking themselves if they can bear it—or whether it’s

worth it!—to watch innocent lives destroyed for the sake of proclaiming their

faith.

Inoue sees Christianity as a nuisance, and Christians as

trouble makers. He compares Christianity to a barren woman who relentlessly

loves someone, but who is unfit to be a wife. Thus he tries every awful trick in

the book to get Christians to recant, and to stamp out Christianity. Rodrigues

and Garupe are tested again and again, right to their breaking points.

Rodrigues, in particular, is at a loss for what to do. He

cannot hear God. He does not know what God would have him do. Rodrigues is

willing to sacrifice himself. But others? What’s the point of causing all this

grief just to refuse to comply with the inquisitor’s wishes?

I’m not quite sure Scorsese ever found it—that angle,

that perspective, that theme, that emotion, that message he was looking for. It’s

not that this movie lacks vision, or fails to pack an emotional punch. Not at

all. It is compelling, heart wrenching, challenging, tragic, thought provoking—all

of that. I just can’t shake the feeling that something’s missing.

In Andrei Tarkovsky’s masterpiece, Andrei Rublev, there’s this one scene of profound religiosity, in

which the iconographer Rublev cradles a young man whose darkest hour has just come.

Without any special effects or explicit nods to the camera, we see that Rublev is

himself the image of God, akin to those he paints—an icon through whom God has

broken his silence, revealed himself, and given comfort to those who seek it. It’s

a sublime aha moment. It’s like, “This Is It”.

There’s nothing quite like that in “Silence”. There’s

plenty to struggle with in the movie. In many ways it’s an admirable meditation

on the demands of faith. But there is no epiphany. The main characters are generally

sympathetic, and there is a vague sense that their steadfastness is somehow

worthwhile, but there is no “This Is It” moment where we really get the point—the

point of what Rodrigues and Garupe are up to, the point of retelling their

story, and indeed, the point of the movie. The why of it all hangs out there unanswered and unaddressed, as if,

even after three decades, the movie wasn’t ready to be made yet.

“Silence” is, in many ways, a very fine movie. It is well

written, directed, acted, shot, composed, and so on. But, like me, you may

leave feeling cold, and in the dark.