Coastal View News

“The Good Dinosaur” starts off with a bit of surprise. 65

million years ago a giant asteroid is jostled from its peaceful orbit and

bumped off into space; it hurtles in a beeline for my home and yours, aka

Planet Earth, speeding at breakneck speed bent on complete annihilation, and … it

misses. It misses! Dinosaurs look up to see a bright streak across the night sky

and then go back to munching on their greens.

This is a good edit for the dinosaurs. No impact, no ice

age, no extinction. And they make good on this windfall—this bit of extra time

to evolve. They shed their backward ways and become civilized. Some learn to

farm, others become ranchers. There are still plenty of baddies—as we all know

civilization doesn’t omit the uncivilized.

But all in all the dinos are doing pretty well.

A case in point: the stars of this movie. They are a family

of farming Apatosauruses (think long neck, long tail, like a Brontosaurus).

Poppa (Jeffrey Wright) and Momma (Frances McDormand) oversee the tilling,

planting, and reaping of their quaint cornfield, while Buck (Ryan Teeple and

Marcus Scribner), Libby (Maleah Nipay-Padilla) and Arlo (Jack McGraw and

Raymond Ochoa) help out.

Well, Buck and Libby help out. Arlo tries. But he is a

knobby-kneed, clumsy, awkward, timid little runt who, despite his best

intentions, fouls things up more often than not. As his brother and sister grow

into sturdy young behemoths and make their marks on the farm, Arlo is left in

the dust. He looks to be soft to the core—un-toughen-up-able.

But that doesn’t stop Poppa from trying. He prods and pushes

Arlo along—sometimes patiently, sometimes not. Again, Arlo tries. But he just

doesn’t seem cut out for the hard life of a dinosaur, or a farmer, or a farming

dinosaur.

Nonetheless, it is tough-as-nails Poppa who gets the worst

of it one day during their desensitivity training. A terrible storm sweeps him

away, leaving the already short-staffed family in a tough spot, and Arlo as

enfeebled as ever. Then when Arlo himself falls into the river and gets swept

off into the wilderness, you think, that’s it he’s done for.

But finding his way back home turns out to be just the

lesson in bravery that Arlo needed. He deals with the elements, fights off

predators, finds shelter, and even gains a companion/pet—a little feral human,

Spot (Jack Bright), who acts just like a dog. Arlo is like Simba in “The Lion

King”, who has to find his own way without his father. Or he is like Littlefoot

in “The Land Before Time”, who has to find his way to safety after losing a

parent. Or maybe it’s more like “Bambi”, or “Finding Nemo”, or “The Jungle

Book”, or … etc.

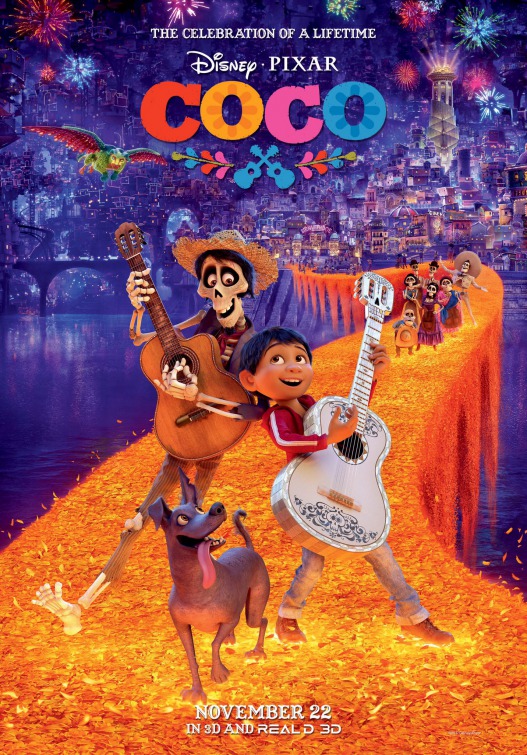

O.K., so there is a lot of recycled material in “The Good

Dinosaur”. In fact, the most original thing about it is the three-minute Pixar

short that comes first and of course has nothing to do with the movie. Still,

“The Good Dinosaur” is sweet. It tells the story—the same ol’ story—pretty

well. It has a few of those blessed Pixar tear-jerking moments. And, best of

all, it has Sam Elliott (think big white mustache and extremely gravelly voice)

playing a cowboy T-Rex.

So while this movie is not as original or inventive or fresh

as one might like, I say it’s still worth it.