Coastal View News

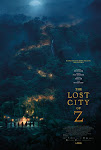

“The Lost City of Z” is an adventure tale, and a

true(-ish) one at that. The exploits it tells of easily rival those of Magellan,

Earhart, Cousteau, Lewis and Clark, and Ahab. It’s the stuff of old, crackly,

black-and-white newsreels about men in safari hats finding hidden temples in

the jungle, with the exciting voiceover spinning yarns of exotic intrigue, ceaseless

peril, and the almost unbearable titillation of what’s next—what’s out there.

In this episode, our hero is Percy Fawcett (Charlie

Hunnam). You wouldn’t have guessed it, but this magnificent specimen started

off as an ordinary British army officer in the early 20th century,

with no medals on his lapel and no obvious paths to greatness.

Until, that is, he is commanded to report to the Royal

Geographical Society for an assignment. There they tell Fawcett that he is to

go on an expedition to South America—Bolivia, to be precise—to help resolve a

border dispute and (ahem) maybe even make England a little coin in the rubber

trade.

Fawcett doesn’t love the idea at first—especially because

he has a wife and young son—but the siren song of adventure soon bends his ear,

and the decision is made.

So he sets off for the Amazon. Unfortunately it’s not a very

pleasant place. What was billed as a vigorous romp through the jungle turns out

to be malarial hell.

Fawcett seems to regret the change of lifestyle, but like

a good Englishman, he keeps calm and carries on. Snakes, piranhas, panthers,

and poison arrows vie to expel him from the jungle, but Fawcett soldiers on.

Just as he and his team (as well as us viewers) are at

their wits end, they stumble across some evidence of a mysterious lost civilization—one

that looks to be far more advanced than anyone thought possible. This is

intriguing, to be sure, but since at this point priority number one is not

dying, the lost civilization remains undiscovered.

Quick cut and they’re back home (And, yes, I do mean

quick cut … there are a bunch of these abrupt, continents-spanning jumps between

the jungle and the English countryside in the movie). Big sigh of relief,

right? Well, actually, as much as he likes his wife and (now) two kids, it does

not take long before Fawcett is itching to get back out there. He wants to find—nay,

he needs to find—that lost

civilization, which he calls “Z” (“Zed” if you’re British).

Z thus becomes his white whale. Fawcett says he wants to

rewrite the history books; he aims to show that white men are not the sole

bearers of dignity; he hopes to upend the dogma and bigotry of Western

colonialism. That’s all very noble, of course. But it’s hard not to see all that

bluster as cover for his thirst for the unknown—for his magnetic attraction to

discovering new things and enduring hardships in naught but the name of

adventure.

But, as with all white whales, there are obstacles. Skeptics,

governments, wars, economies, bigots, and even families all stand between

Fawcett and his lost city of Z.

As I said, this is the stuff of legend—of yarns spun in

old newsreels.

Yet this yarn is spun a bit differently. Whereas those

old newsreels gleam of Classic Hollywood—of romance, hope, optimism and a world

full of goodness—“The Lost City of Z” takes on a decidedly more realist tone.

The peril isn’t reducible to mere excitement; it isn’t cartoonish and unimposing

ala “Indiana Jones”. The aches, pains and conflicts in this movie feel real, and at times, unbearable.

This actually had me worried in terms of the tone of the

movie. The question is: Does realism pair well with an adventure tale of this

sort? One could make the case that by portraying the horrors of nature, and by complicating

the virtue of our hero’s motives with the fact that he abandoned his family, and

by showing how nasty people, governments, and other organizations can be, this

movie yields a more complex, nuanced version of an adventure story. Fine. But

these features necessarily dilute so much of what is appealing about Earhart, Cousteau,

and yes, even Indiana Jones, which is their pure spiritedness—their simple,

totally uncomplicated and completely unencumbered drive to get out there and

discover.

So I was worried about “The Lost City of Z”. I thought, “This

movie can’t have it both ways—it can’t be both

a crackly-newsreel adventure tale and

a hyper realistic drama.” But, by the end, I got on board. Partly that’s

because the movie ends up shedding its realist yoke. But also, realistic or

not, the last quarter of the movie just does a really nice job of striking that

pleasing chord of great adventures. It makes you get it. It makes you see the

point of setting sail. It makes you feel

like it’s worth getting out there and doing it, whatever “it” may be.